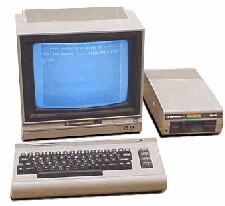

In the late 1970s and early 1980s along came {{drum roll}} the personal computer. Although the infant World-Wide Web really didn't roll out until the mid-1990s, as soon as I bought my very first computer for a hundred bucks, the

legendary Timex Sinclair 1000, it changed my life forever. Despite its pathetic specs, horrible membrane keyboard, and black and white TV output, it's now a primitive museum piece, but back then it was revolutionary. While others took different paths, to early Apples and the IBM PC (if you could cough up about three or four grand), I took the Commodore road..

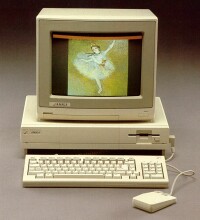

first a VIC-20, then a Commodore=64, and later, the way-ahead-of-its-time-and-probably-still-is Amiga, which debuted in 1985. Graphical games of all description were a huge draw to the Amiga, and oddly enough, games were both what made it special and (along with rampant software piracy) ultimately killed it, as Amiga garnered the reputation as a gaming machine, not a "serious" computer, although it could do virtually anything a computer needed to do, Commodore just didn't know how to properly market it. At all. If you were, or still are, an Amiga owner, you'll remember the crack about Commodore's marketing motto: "Ready! Fire! Aim!"

Hey, guess what sells expensive, ultra fast PCs these days? You guessed it – gaming. Modern graphics-intensive games require a lot of computing horsepower.

Kill Troll, take Gold key

Computer gaming has advanced to a level that I have to admit is often even beyond me. IÂ’m not much of a game player any more, but these days people have short attention spans, and getting deeply involved in a novel-length text adventure with which you interact purely by typing has become a lost art.

But long before interactive Web gaming, before 3D and even before 2D computer arcade and adventure games, before any of what have today, there was "Interactive Fiction."

I spent a ridiculous amount of time (and money) playing Scott Adams Interactive Fiction cartridge games on my old VIC-20, and later, playing them online on CompuServe over a 300 baud modem. I'd be ashamed to admit the kind of online bills I racked up doing that.

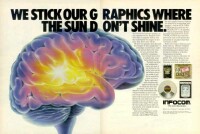

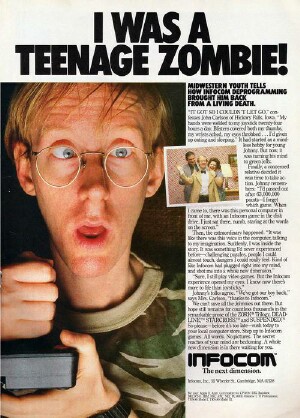

The whole genre of Interactive Fiction text-based games exploded when Infocom hit the scene; their wizards produced a fantastic series of totally text-based computer games where YOU were the main character, tossed into some strange, unfamiliar place, with few clues as to what you were supposed to do.

No graphics, no sound effects, no 3D, no blood and guts, no joystick required - Infocom games were literally a novel you interacted with, simply by typing commands in English.

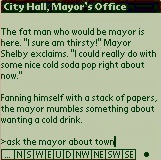

There was some mood-setting art on the box, and their first series of boxed games (which are now VERY valuable.. did you save yours? Check out eBay and be astounded at what collectors are paying for them).. came in impressive packages with interesting, sometimes mysterious props and goodies inside to create an atmosphere, to spirit you off to some imaginary time and place, where you explored a strange environment and interacted with human, alien, even robotic characters by typing text, and reacting to text responses. You'd "talk" to the game with simple, logical English commands – "Go North" or "Open the mailbox", and each command you entered was replied to with the game's response.

If a door was locked, you'd have to find a key to open it. If there was a letter in the mailbox, you'd type commands to take it out and read it. Almost everything was a clue to lead you to the next action to take, or, in many cases, a completely false lead to throw you off the track.

Put away your mouse; you didn't need it. Just like the best radio drama, these games' imagery was totally conjured up by your mind. Legions of people enjoyed Infocom games. They even made and sold hint books you could turn to when you were totally stuck, in which you would wipe a "magic yellow pen" across a "Hey, this is where I'm stuck!" sentence and reveal the answer as to what to do next.

Run an Infocom game, and after a brief intro which explained your surroundings, you were pretty much on your own to figure out what you were supposed to accomplish.

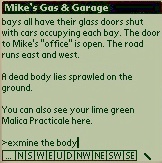

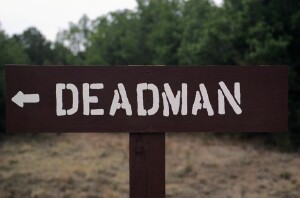

You might find yourself alone on a dusty road, facing some creepy old abandoned shack, and by typing plain English commands like "Go North, open door", the game would respond with something like "you approach the shack and slowly open the rotted, creaking door, brush away the cobwebs and take a few steps inside to explore. It's dark and smells musty inside." So you had to type more commands and see if you could find a candle or an oil lamp and some matches, and so on.

The beauty of Interactive Fiction was that how it looked was however you wanted it to look – your mind's eye built the picture of your surroundings, and every person "saw" it differently. There weren't really any rules as to what you could do and in what order they had to be done. All you knew is that an end-game lurked out there somewhere, and by simply typing commands, the game responded with text that conjured up more mental images, clues, false leads, red herrings, or what Alfred Hitchcock liked to call the "MacGuffin" – some object that seemed like it was important to advance the plot, but really wasn't.

Like radio drama, except YOU'RE in it..

The whole Infocom "Interactive Fiction" experience was not unlike classic Old Time Radio, whose devotees often refer to as "The Theatre of the Mind."

Before TV came along and put everything right in your face, you tuned across the AM dial and listened to Marshall Dillon's adventures in "Gunsmoke's" Dodge City, or detective shows like Philip Marlowe, Sam Spade, Johnny Dollar and countless others.. other-worldly science fiction like X-Minus One, or shivered in fear listening to Arch Obeler's classic "Lights Out!" Horror tales. It truly was a Golden era.

You never SAW Obeler turn a human being inside out, but by his ingenious use of a sound effects man slowly pulling a wet rubber glove off his hand, you HEARD what sounded like it.

So the Golden age of Radio forced you to paint mental pictures of the characters, and their surroundings. As Marshall McLuhan so aptly explained it, radio, forcing you to use your brain, is a "Hot" media, while TV, which lays it all out in front of you, is a "Cool" media.

Howard Sherman brings back Interactive Fiction.

So back to the program at hand – Infocom's wildly imaginative and involving games gave way to graphics-laden gaming, and an era passed. Or so it seems. But it's back with a vengeance, thanks to one very creative and visionary entrepreneur.

More than 25 years after Infocom's first game, "Zork" appeared, this creative genius is using todayÂ’s technology to reinvent the Interactive Fiction genre.

An original Zork fan, Howard Sherman founded Malinche Entertainment with the goal of introducing interactive fiction to an entirely new generation of fans.

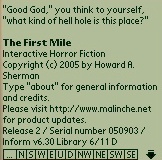

You can access and play Malinche's titles with any personal computer, laptop, PocketPC or PalmOS handheld, iPod, and other selected cell phone models. His games play just like the Infocom games you remember.

Malinche's games are brand new novel-length tales, not re-hashes of the old Infocom classics.

But can interactive fiction move beyond just a small niche audience? Sherman is betting it can. For years, cell-phone enthusiasts have been hacking their phones to play old-fashioned games from the Commodore=64 era. In many ways, the text-game genre is better suited for small handheld devices than modern graphic-based games. Rather than shrinking down graphics-heavy screens intended to fill a monitor, and instead of needing a computer with more CPU than a Dodge Hemi has horses just to play graphics-intensive games, Sherman's imaginative text games scroll good old plain text .. just like Infocom's classics.

To test out Sherman’s theory, I tried out his first title, an imaginative tale called “The First Mile.” Installation required just two pieces: The included PalmOS "Frobnitz" game interpreter engine, and the game file itself, about 400k.

Interactive fiction unfolds before you in a narrative with plot twists and turns, just like the old “Choose Your Own Adventures Novels” of the 1980s.

“The First Mile” is approximately the same size as a full-length novel in content, but instead of being passively entertained by a traditional print novel, you’re the protagonist, deciding when, where, why and how the story will unfold. Maps of all the game’s territory are included with the download or the fancier (and more expensive) CD “Folio” versions, but the game itself is 100% text.

As Sherman explains it:

Interactive fiction is the fusion of books and technology. This fusion taps into the hidden power of today's computers, handhelds and smartphones to deliver the novel of the future that glues you to every turn the story takes. What sets our fiction titles apart from conventional fiction books is that our titles are interactive. Every title we offer engages your mind and imagination as you make your way through the story and interact with the other characters in the title as the plot unfolds in response to every move you make.

If you're thinking Malinche publishes e-books you're on the right track but that doesn't tell the whole story. Consider that our interactive fiction titles are fiction e-books you can talk to in conversational English. That's the nature of Malinche interactive fiction; every fiction book we offer actually demands your participation at every turn the story takes.

That's because you are the main character in the story!

On a Palm, the game works similarly to how it functions on a desktop. For PalmOS, it'll play on virtually any model from the oldest Pilots to the newest Treos. On those models without a physical keyboard, there are some handy on-screen "accelerators" to minimize graffiti usage AND make the best use of the small screen, like the compass point direction bar, user editable command list, user editable verb list, and double tapping words already on the screen to select them for the text input line.

With long text, the scrolling story pauses and you tap once on the screen to get the next screen full, but you can also use the game's scrollback feature. Treos, with their full keyboards, let the player type in all their commands, without Graffiti scribbling.

Thanks to the shortcut buttons, you can tap on the action you want to take (tap on "East" to go East, click on "ask", etc.), or write / type your commands with your stylus or keyboard, thus telling the game exactly what you want to do. The end result is the same play-ability you'll find in the Windows or Mac version. PocketPCs work the same way and Malinche games are also certified for Windows Mobile 5.0.

Malinche Entertainment boasts that its first three games have sold more than 100,000 copies — a minute, fractional piece of the multibillion-dollar computer gaming market. But enough to indicate that there just may be a legitimate market for text games for the first time in over 15 years.

Similar to the growing legions of Old Time Radio fans who are sick of the endless garbage TV dishes up, a lot of computer game players are looking for something new, and in the case of Malinche's Interactive Fiction games, what was old (Infocom-style game play) is now new again. The circle of life, or something like that..

"The First Mile" is a horror story. As Malinche describes it:

Like most horror stories, things start out simply enough. You're driving cross country to relocate to a new job. Your gas tank is almost empty and your stomach is too. Fortunately, an exit off the interstate comes up right there so you turn off to fill your car and your grumbling stomach.

Just as you pull up to the gas station on the outskirts of town, a crazed man shoots the gas attendant dead. At point-blank range. With a shotgun. Then he turns the shotgun towards your car and takes aim at you! Your heart stops as he pulls the trigger! The roar of the shotgun and the tinkling smashing glass fills the air. Luckily, you ducked first. Your unknown nemesis raises the powerful weapon right at you, through the windshield and all. He pulls the trigger but nothing happens. Fiddling with the weapon doesn't help. The bedraggled killer glares at you before he runs off.

What happens next? Only you can decide. The First Mile is a work of Interactive Fiction where anything is possible and everything is worth a try. You are the main character in this horror story and every move you make will either lead to your escape....or your death.

Every Folio Edition of The First Mile comes with a genuine compass and a hand-written sticky note; both of which are a part of the actual story. The Folio CD contains the story file and all software necessary to run your game on pretty much any modern computer any Palm you might own, iPods and Symbian phones too.

Explore Malinche's site. If Horror isn't your thing, they offer other genres of Interactive fiction.

There's also a page filled with free stuff to explore, including free games, guides, Parental advice about gaming for kids, a chat room, articles by Howard, and a ton of other goodies.

Instant Digital Downloads of The First Mile are $24.95. If you prefer the fancier mailed Folio Edition on disc with the aforementioned sticky note and compass, that's ten bucks more, and you can order it on their site and use PayPal, or buy it over the phone.

Next Page: Conclusion >>